07 December 2022

School holidays have begun for UK universities, and what better way to celebrate it than to start with a CTF? This time, I took part in HTB University CTF 2022. This post will document my thought process in solving the challenge Wizard’s Diary. As the challenge is fairly complicated and I am not very good at technical writing, there is a TLDR at the end that summarises my approach.

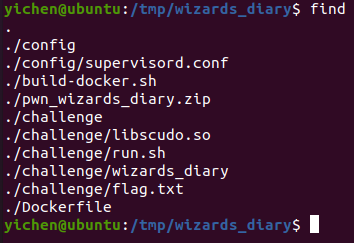

Fig 1. Files given

Fig 1. Files given

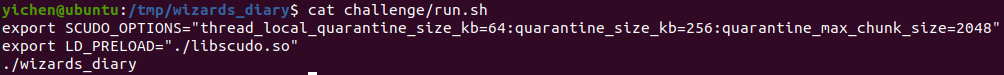

Fig 2. Contents of run.sh

Fig 2. Contents of run.sh

We are given fairly standard files to set up the docker container for the CTF challenge. What immediately caught my eye was the dynamic library provided named libscudo.so. Looking at the contents of run.sh, it is evident that it is loaded into the challenge binary to provide some additional level of difficulty.

Fig 3. Scudo

Fig 3. Scudo

Doing a quick Google search, we see that the Scudo project is a hardened heap allocator that is meant to replace the default PTMalloc allocator provided by Glibc and provide protections against common heap vulnerabilites such as UAF and heap buffer overflow. Time to analyse the given binary.

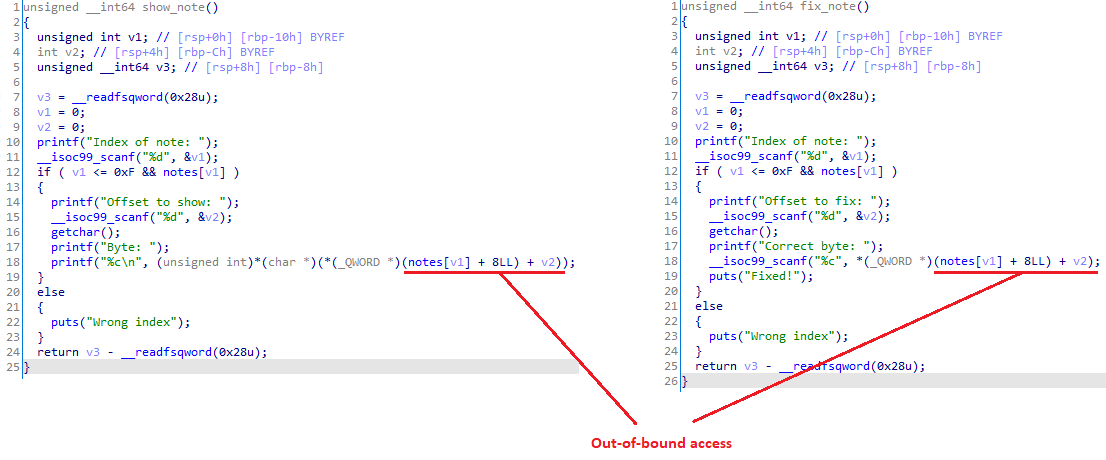

Fig 4. Note functions

Fig 4. Note functions

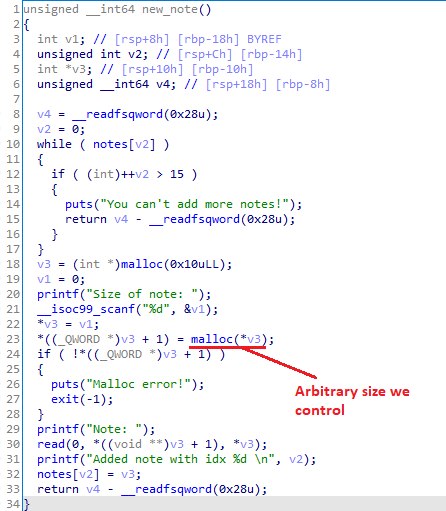

Fig 5. New note

Fig 5. New note

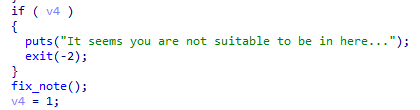

Fig 6. You only got one shot

Fig 6. You only got one shot

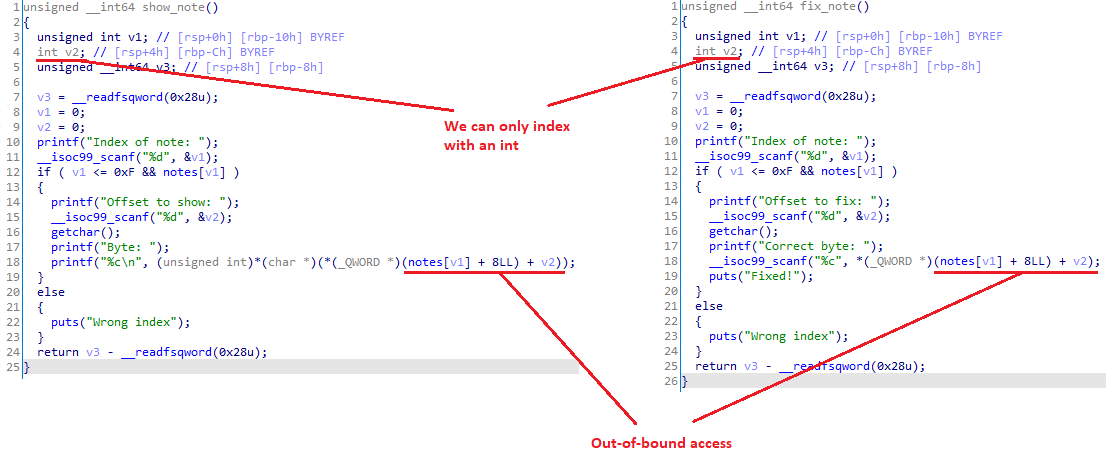

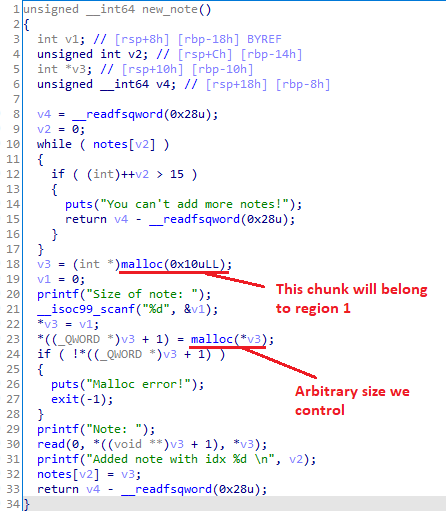

In new_note, we can allocate a heap buffer of arbitrary size. With the function show_note, we can then do unlimited out-of-bound single-byte reads from the aforementioned buffer. With fix_note, the situation gets interesting, as we only have one shot at writing a byte out-of-bound.

Fig 7. Login function

Fig 7. Login function

Fig 8. Dammit

Fig 8. Dammit

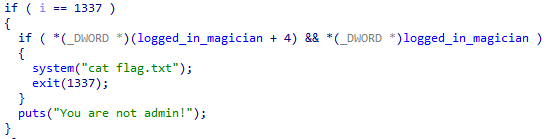

Inside the function login, we see that it makes a heap allocation of size 0x1f48 and stores it in the global variable logged_in_magician. Notice that the first 2 DWORDs have been intentionally zeroed out. To get the flag, we have to make them both non-zero, as seen in the main function. It becomes clear why they chose 2 instead of 1 DWORD: our single-byte write primitive cannot be used directly to get flag.

To begin exploitation, we have to first understand how Scudo works. For this post, I will be using commit 1e33330e29e7 from the LLVM Project. We will be using the standalone version of Scudo under compiler-rt/lib/scudo/standalone.

NOINLINE void *allocate(uptr Size, Chunk::Origin Origin, // line 298

uptr Alignment = MinAlignment,

bool ZeroContents = false) {

/* Omitted for brevity*/

if (LIKELY(PrimaryT::canAllocate(NeededSize))) {

ClassId = SizeClassMap::getClassIdBySize(NeededSize); // line 353

DCHECK_NE(ClassId, 0U);

bool UnlockRequired;

auto *TSD = TSDRegistry.getTSDAndLock(&UnlockRequired);

Block = TSD->Cache.allocate(ClassId); // line 357 (Primary allocation)

/* Omitted for brevity*/

}

if (UNLIKELY(ClassId == 0)) // line 371 (Secondary allocation)

Block = Secondary.allocate(Options, Size, Alignment, &SecondaryBlockEnd,

FillContents);

Firstly, let’s begin with the allocate function at combined.h:298. After a bunch of checks, the function either makes an allocation using either the primary (line 357) or secondary (line 372) allocator. The wiki for the project already explains the difference between these two, but essentially, if allocations are above 0x20000 bytes for this challenge, it is handled by secondary, otherwise most likely primary. We will need both to solve this challenge.

In line 353, SizeClassMap::getClassIdBySize is called to get the class ID corresponding to the size we require. This will come in very handy soon.

void *allocate(uptr ClassId) { // line 97

DCHECK_LT(ClassId, NumClasses);

PerClass *C = &PerClassArray[ClassId];

if (C->Count == 0) {

if (UNLIKELY(!refill(C, ClassId))) // Important code to refill cache

return nullptr;

DCHECK_GT(C->Count, 0);

}

// We read ClassSize first before accessing Chunks because it's adjacent to

// Count, while Chunks might be further off (depending on Count). That keeps

// the memory accesses in close quarters.

const uptr ClassSize = C->ClassSize;

CompactPtrT CompactP = C->Chunks[--C->Count];

Stats.add(StatAllocated, ClassSize);

Stats.sub(StatFree, ClassSize);

return Allocator->decompactPtr(ClassId, CompactP);

}

Tracing TSD->Cache.allocate leads us to local_cache.h:97. How caching works is not very important here; rather, we would want to know how the cache is refilled.

TransferBatch *popBatch(CacheT *C, uptr ClassId) { // line 100

DCHECK_LT(ClassId, NumClasses);

RegionInfo *Region = getRegionInfo(ClassId);

ScopedLock L(Region->Mutex);

TransferBatch *B = popBatchImpl(C, ClassId);

if (UNLIKELY(!B)) {

if (UNLIKELY(!populateFreeList(C, ClassId, Region)))

return nullptr;

B = popBatchImpl(C, ClassId);

// if `populateFreeList` succeeded, we are supposed to get free blocks.

DCHECK_NE(B, nullptr);

}

Region->Stats.PoppedBlocks += B->getCount();

return B;

}

NOINLINE bool refill(PerClass *C, uptr ClassId) { // line 209

initCacheMaybe(C);

TransferBatch *B = Allocator->popBatch(this, ClassId);

if (UNLIKELY(!B))

return false;

DCHECK_GT(B->getCount(), 0);

C->Count = B->getCount();

B->copyToArray(C->Chunks);

B->clear();

destroyBatch(ClassId, B);

return true;

}

TransferBatch *popBatchImpl(CacheT *C, uptr ClassId) { // line 533

RegionInfo *Region = getRegionInfo(ClassId);

/* Omitted for brevity*/

We then trace from refill on line 209 to popBatch (line 100) and subsequently popBatchImpl (line 533) in primary64.h. primary64.h provides code for the primary allocator for 64-bit systems.

void init(s32 ReleaseToOsInterval) { // line 63

DCHECK(isAligned(reinterpret_cast<uptr>(this), alignof(ThisT)));

DCHECK_EQ(PrimaryBase, 0U);

// Reserve the space required for the Primary.

PrimaryBase = reinterpret_cast<uptr>( // line 67

map(nullptr, PrimarySize, nullptr, MAP_NOACCESS, &Data));

u32 Seed;

const u64 Time = getMonotonicTime();

if (!getRandom(reinterpret_cast<void *>(&Seed), sizeof(Seed)))

Seed = static_cast<u32>(Time ^ (PrimaryBase >> 12));

const uptr PageSize = getPageSizeCached();

for (uptr I = 0; I < NumClasses; I++) { // line 75

RegionInfo *Region = getRegionInfo(I);

// The actual start of a region is offset by a random number of pages

// when PrimaryEnableRandomOffset is set.

Region->RegionBeg = getRegionBaseByClassId(I) +

(Config::PrimaryEnableRandomOffset

? ((getRandomModN(&Seed, 16) + 1) * PageSize) // random offset :(

: 0);

Region->RandState = getRandomU32(&Seed);

Region->ReleaseInfo.LastReleaseAtNs = Time;

} // line 85

setOption(Option::ReleaseInterval, static_cast<sptr>(ReleaseToOsInterval));

}

To understand how the primary allocator works in general, there are a few important functions to focus on. First, we need to begin with init on line 63. Line 67 indicates that we are reserving a huge main page of memory, and the for loop from line 75 to 85 splits the page into regions based on the aforementioned class ID. To make things harder, it adds a random offset of between 1 to 16 page sizes (4096 bytes).

In other words, chunks of the same size will be grouped in the memory regions, and regions are separated by guard pages in between. For this CTF’s configuration, the regions have a $2^{32}$ byte gap between them.

NOINLINE bool populateFreeList(CacheT *C, uptr ClassId, RegionInfo *Region) { // line 563

/* Omitted for brevity*/

constexpr u32 ShuffleArraySize =

MaxNumBatches * TransferBatch::MaxNumCached;

CompactPtrT ShuffleArray[ShuffleArraySize];

DCHECK_LE(NumberOfBlocks, ShuffleArraySize);

const uptr CompactPtrBase = getCompactPtrBaseByClassId(ClassId);

uptr P = RegionBeg + Region->AllocatedUser;

for (u32 I = 0; I < NumberOfBlocks; I++, P += Size)

ShuffleArray[I] = compactPtrInternal(CompactPtrBase, P);

// No need to shuffle the batches size class.

if (ClassId != SizeClassMap::BatchClassId)

shuffle(ShuffleArray, NumberOfBlocks, &Region->RandState); // line 618, order of chunks randomised

for (u32 I = 0; I < NumberOfBlocks;) {

// `MaxCount` is u16 so the result will also fit in u16.

const u16 N = static_cast<u16>(Min<u32>(MaxCount, NumberOfBlocks - I));

// Note that the N blocks here may have different group ids. Given that

// it only happens when it crosses the group size boundary. Instead of

// sorting them, treat them as same group here to avoid sorting the

// almost-sorted blocks.

pushBlocksImpl(C, ClassId, &ShuffleArray[I], N, /*SameGroup=*/true);

I += N;

} // line 626

/* Omitted for brevity*/

}

We are not done with the initialisation just yet. To populate structures for memory allocation to start working, we need to look at populateFreeList on line 563. The two important lines are lines 618 and 626. Essentially, it splits a memory region into equally sized chunks, before shuffling their order and passing them to pushBlocksImpl. Unlike in PTMalloc, chunks will hence be allocated in random order.

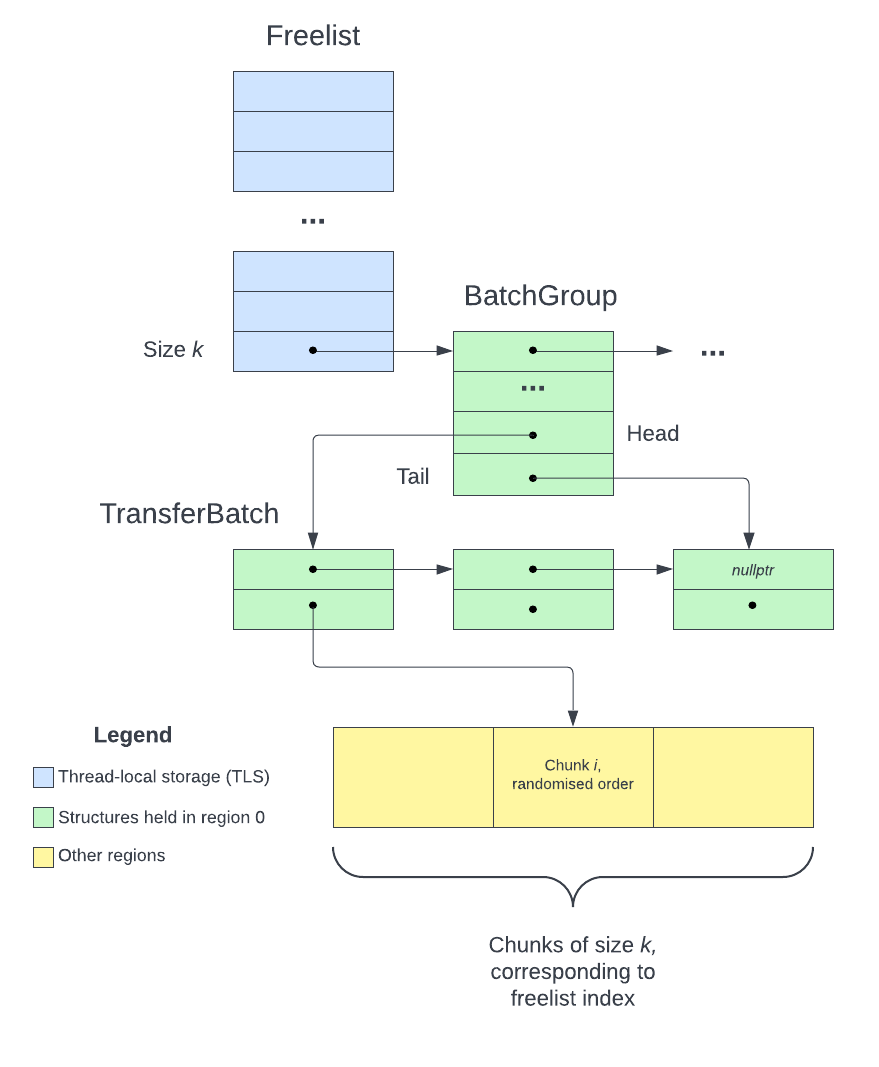

Fig 9. Primary allocation

Fig 9. Primary allocation

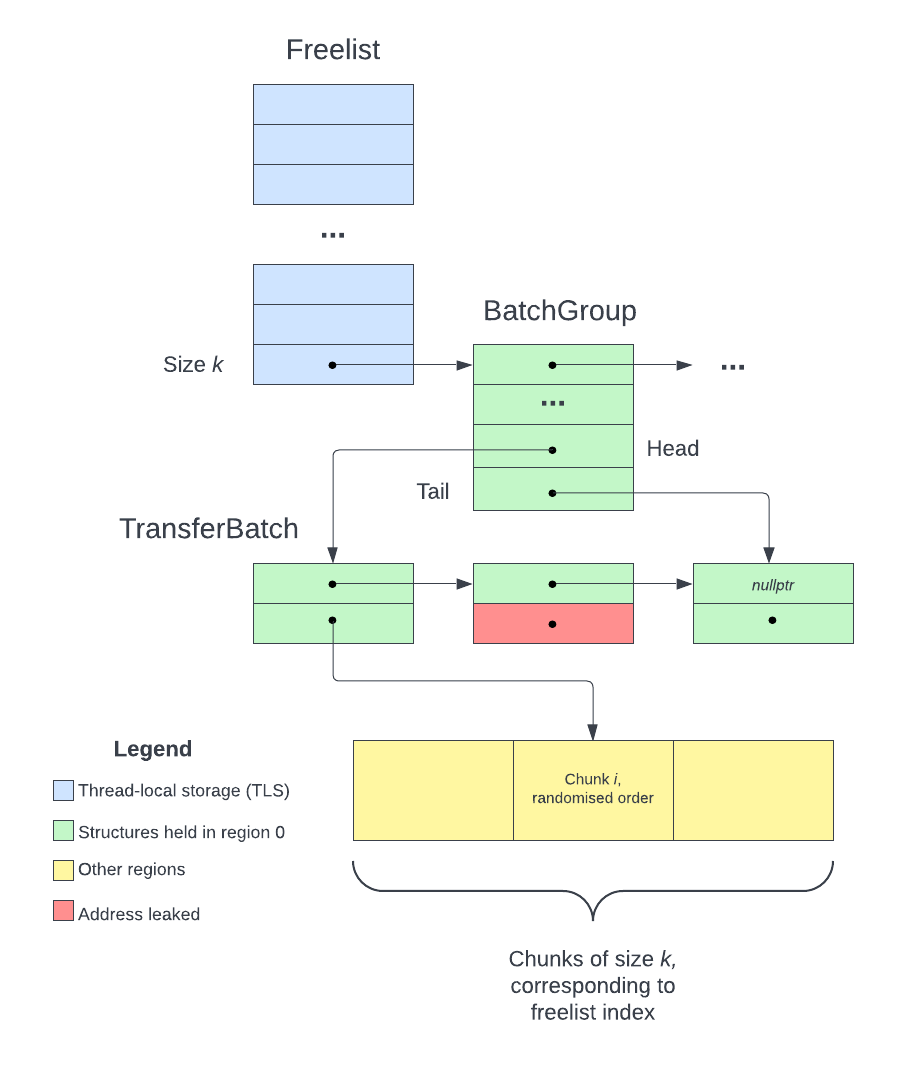

Based on the code in pushBlocksImpl itself, I have came up with the above (simplifed) diagram for primary allocation. The steps to find an available chunk of size sz are as follows:

sz and index into the Freelist to find the BatchGroupBatches

In actuality, there can be a linked list of BatchGroups for a class ID and a TransferBatch can contain more than one available chunk. During the actual CTF however, the structures usually have a single element, and hence I simplified the explanation for easier understanding.

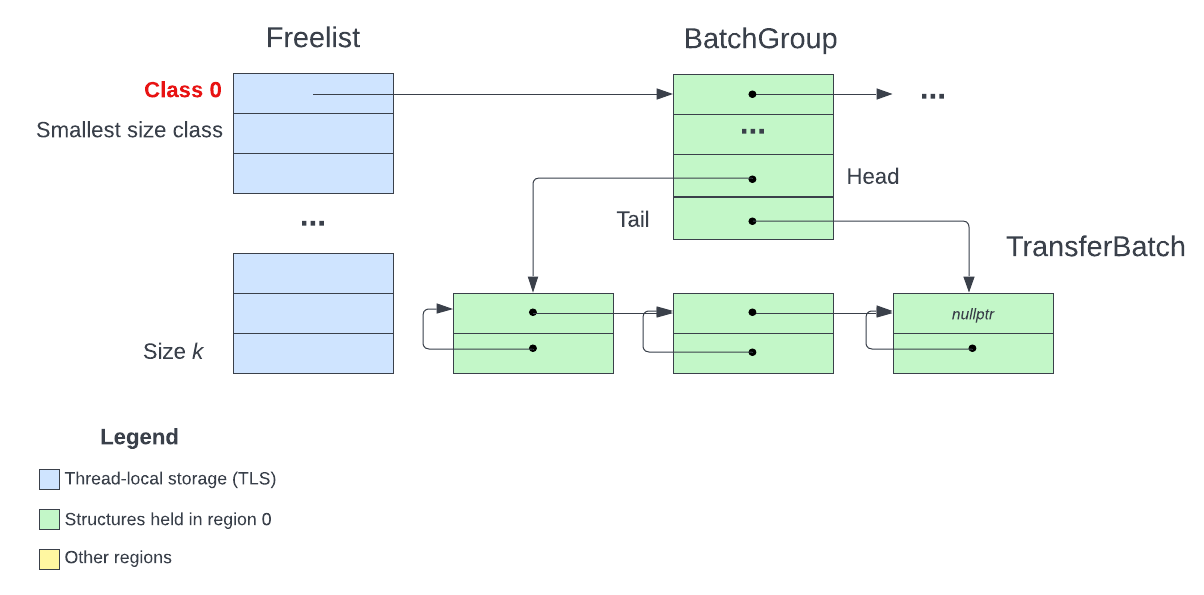

Fig 10. Class ID 0

Fig 10. Class ID 0

One may wonder: if the allocator uses data structures for management, where does it store those structures? The answer is in class ID 0. Recall that reserved memory is split into regions for each size class. The smallest chunks are stored in class ID 1, while 0 is reserved for the allocator’s internal structures. This is the BatchClassId that can be seen throughout the code in primary64.h. For our exploitation, reading and writing into this region 0 will be useful.

Fig 11. Signed integer index

Fig 11. Signed integer index

We have now encountered an issue. Since regions are ~$2^{32}$ bytes apart, our OOB read and write both cannot access other regions, as the signed int used to index into our heap buffer has a range of $-2^{31}$ to $2^{31}-1$. There is no way of allocating a chunk for class ID 0 either, so we seem to have no way of writing into region 0. This is where secondary allocations come in.

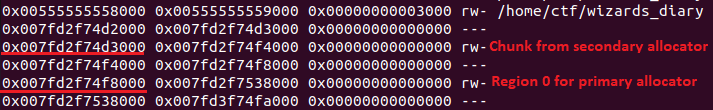

Fig 12. Secondary location just before region 0

Fig 12. Secondary location just before region 0

I did not go in-depth into the secondary allocator’s code, but it somehow reliably places my heap buffer right before region 0. All we have to do is just make a big enough allocation, which is 0x20000 bytes and above. Now, we can do OOB read and write into region 0.

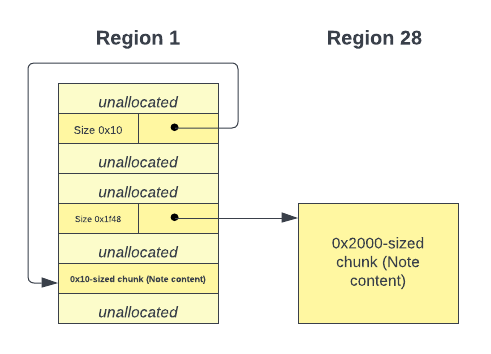

Fig 13. The structure holding pointers belong to 0x10-sized region (region 1)

Fig 13. The structure holding pointers belong to 0x10-sized region (region 1)

Fig 14. The two regions

Fig 14. The two regions

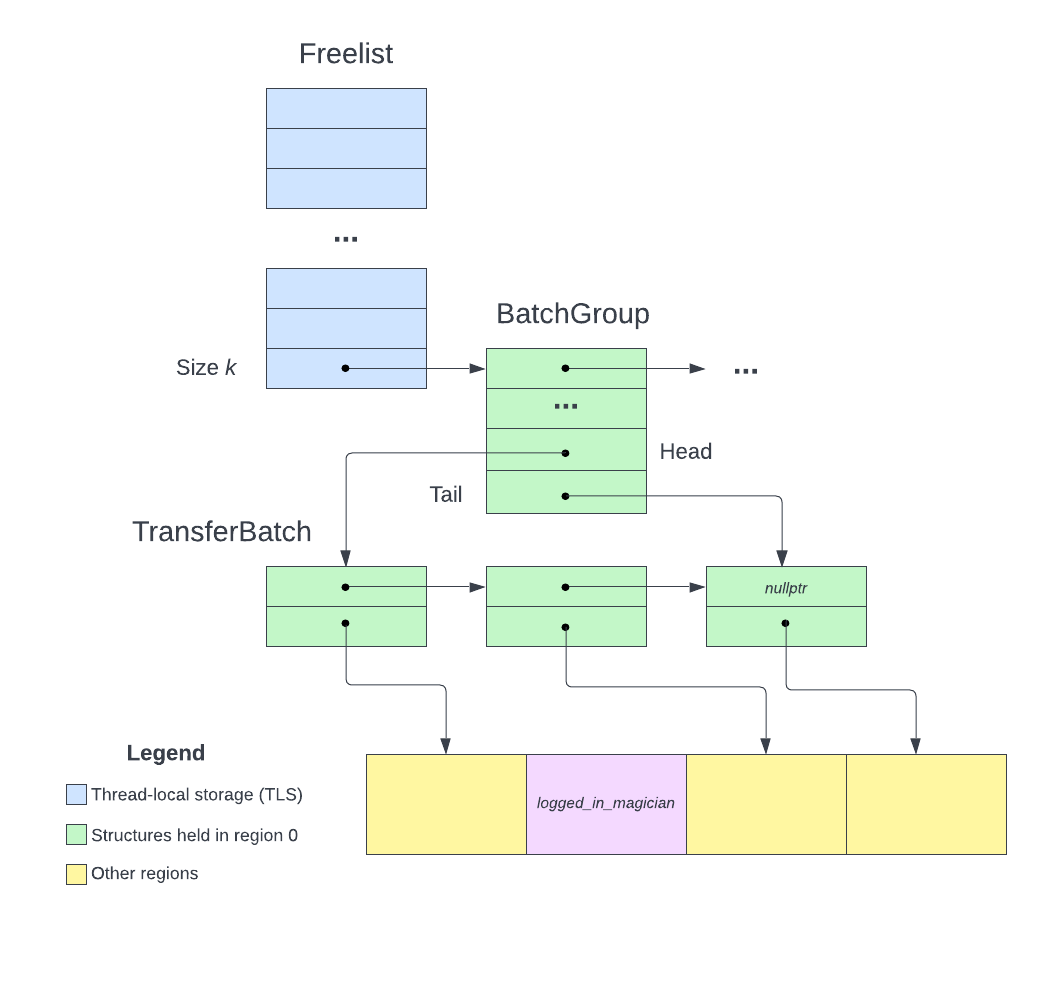

The chunk used in logged_in_magician was allocated by malloc(0x1f48), and hence belongs to the size class for chunks of size 0x2000, which is region 28 (based on gdb). We would want to leak a pointer to this region. We start by making a few allocations of size 0x2000, and their pointers will be stored in 0x10 sized chunks. We then allocate a note with content of size 0x10 and use OOB read to scan before and after that buffer for pointers to region 28.

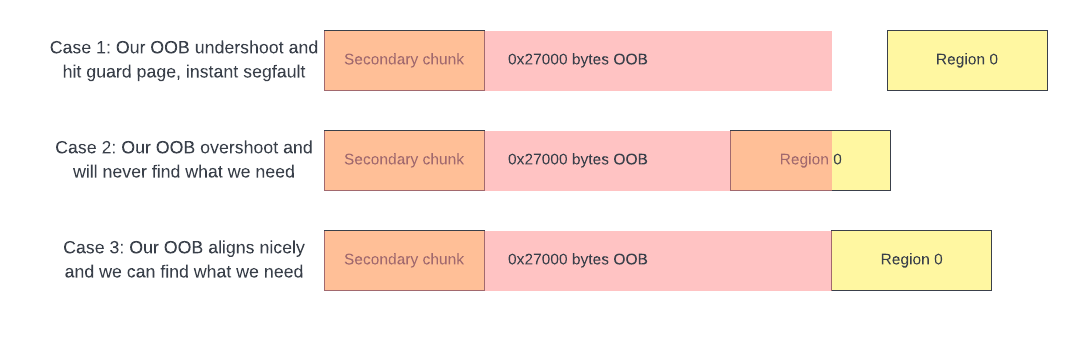

Fig 15. Possible cases

Fig 15. Possible cases

We can now start searching at a fixed offset (e.g. 0x27000) from the secondary chunk to index into region 0 to find pointers to region 28. This step has around 1/16 chance of working as region base randomisation causes the gap between the secondary allocator buffer and region 0 to vary between runs.

Fig 16. We leaked the location in a TransferBatch node

Fig 16. We leaked the location in a TransferBatch node

The pointers we will find are pointers to available size 0x2000 chunks in region 28. It is pretty much game over from here as we now know the location of a node in the TransferBatch linked list. Due to time constraints during the CTF, the following approach is not fully theoretically sound and is based on trial and error from testing.

Fig 17. No TransferBatch points to logged_in_magician

Fig 17. No TransferBatch points to logged_in_magician

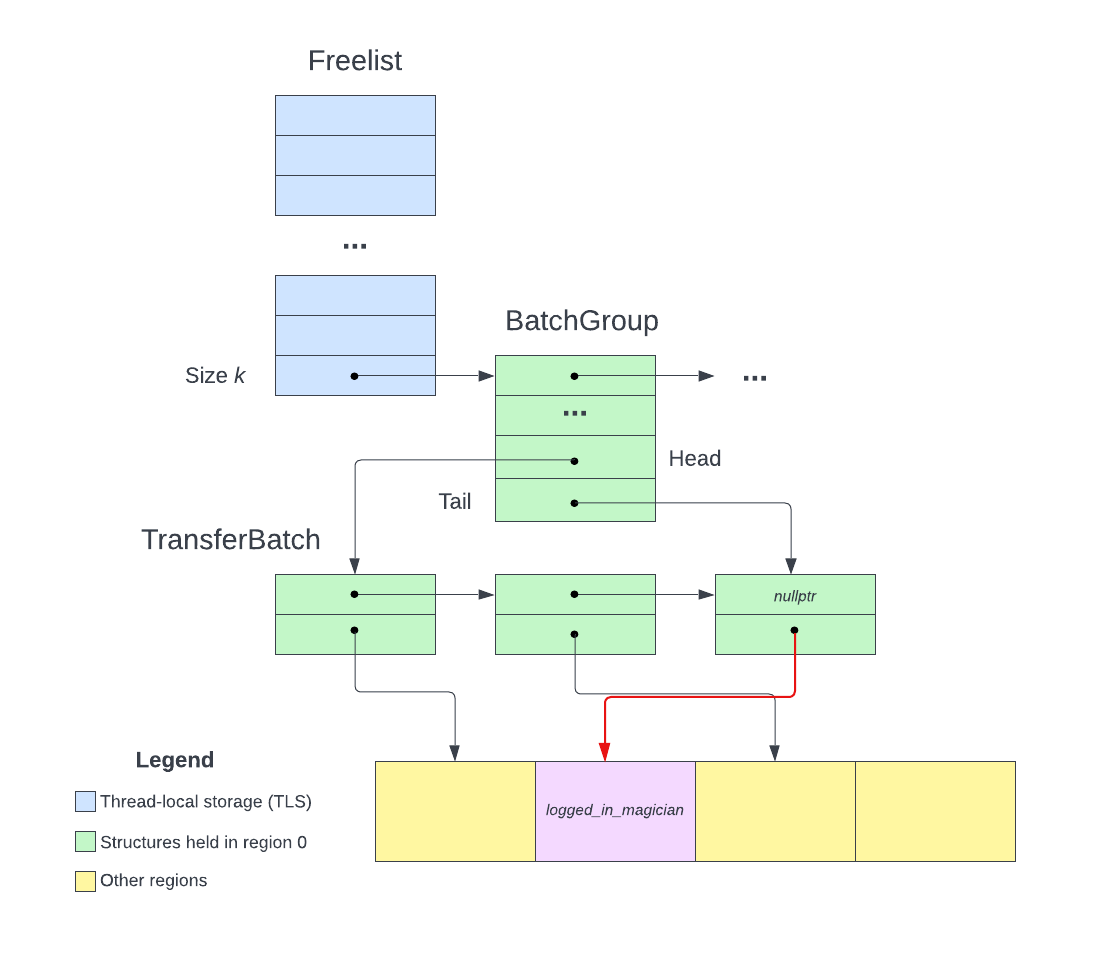

We can traverse the linked list forward as per normal, and also “traverse” backwards because the TransferBatch chunks (size 0x80) are all adjacent in memory. From this, we gather the addresses of all the chunks in region 28. For some reason, the chunk used in logged_in_magician will be missing from the list. We just have to see which chunk in the region is missing from our list to deduce its address.

Fig 18. Corruption complete

Fig 18. Corruption complete

We then find a free chunk in the linked list that has a byte edit distance of 1 with the logged_in_magician chunk and modify the pointer to that chunk using our one-shot fix_note OOB write. From the perspective of the allocator, the already-allocated chunk used by logged_in_magician is now available again.

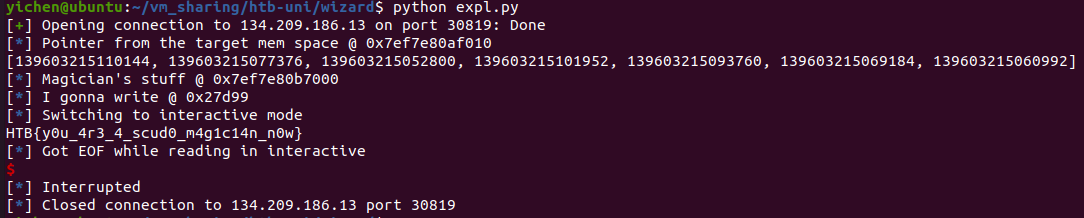

Fig 19. Pwned

Fig 19. Pwned

Now, all I have to do is to allocate a couple of 0x2000 sized chunks. One allocation will return the same chunk used by logged_in_magician and I can write into it, hence giving me the flag.

TLDR:

logged_in_magician

logged_in_magician chunk in new_note using note contentsI may have been out of practice, but this challenge has been one of the tougher ones I’ve seen in a while. To me at least, solving the challenge meant getting a decent level of understanding of the Scudo allocator, which could only be done by reading and understanding quite a bit of foreign source code within CTF duration. That was not easy. Shoutout to my wonderful teammate Nyx for her support during the CTF ![]() .

.

Exploit linked here, it is pretty unstable, but hey, it works.